- Home

- Christine Lahti

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness Page 7

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness Read online

Page 7

I thought for sure that once he got to know Tommy, my father would realize just how uninformed he’d been. But instead I found out how pernicious unconscious prejudice can be. Many years after we married and had three young children, Tommy and Dad had an ongoing joke about which college football team was better—Ohio State or Michigan.

“Ohio is clearly superior, Ted. They’re going to trounce your pathetic Wolverines!” teased Tommy, during a visit at my parents’ place. He could have cared less about either team.

My dad laughed. “Ha, ha, ha, over my dead body!”

“You know what, Ted?” Tommy responded. “I so believe in my beloved Buckeyes that I’m willing to wager a whopping six dollars that they win.”

Michigan won. Dad gloated and teased Tommy the rest of the night, all with warm humor.

For several years afterward Tommy would taunt my father back by saying “Oh, hmmm, I just don’t seem to have that six bucks on me right now, but I know that Ohio will beat your crappy team this time.” After about three years of this banter, Dad asked to speak with Tommy alone, down in the garage of our recently purchased home.

“Yeah, Tommy, you know you still owe me six dollars from that bet we made,” declared Dad, sucking repeatedly on his pipe. “Maybe you don’t think you have to honor that, but I just hope you aren’t teaching my grandchildren that it’s okay to welch on a bet.”

My husband grabbed his wallet, yanked out six singles, said “Here’s your money, Ted,” and walked away. He came upstairs to our bedroom and paced back and forth, trying to process the staggering audacity of this mostly absentee father giving him parenting advice.

After this confrontation, Tommy and I both decided that we were just going to have to accept my dad’s limitations. Though he loved Tommy, my father’s coded anti-Semitism was part of his DNA, probably handed down from his parents, who in turn learned it from theirs. Admittedly, when Tommy and I first met, I jokingly referred to gefilte fish as mystery Jew-food and considered it a slippery slope to payot and those big black furry hats.

Neither Tommy nor I were at all religious as adults, but after becoming a couple we celebrated both Christmas and Hanukkah together, although to vastly different degrees. I remember one of our first Christmas Eves after we had kids. As soon as we all decorated our towering Frazier fir tree, which smelled like a pine forest, I rummaged through our stacks of boxes and found some sleigh bells.

With the Mormon Tabernacle Choir belting “O Holy Night” in the background, I said, “God, Tommy, remember when my dad asked you how ‘your people’ celebrated Christmas?” We both laughed. Sipping my eggnog, I then asked him if he wouldn’t mind going up to the attic, shaking the bells, and stomping around so the children would believe Santa was on the roof. After they went to bed, as I placed the large quantity of meticulously wrapped presents under our tree, I pointed to the plate of freshly baked Christmas cookies. “Hey, Tommy, could you please take a few bites so the kids will think that Santa snacked on them?”

Tommy was a good sport and went along with all of it, and I loved watching as he seemed to get swept up in the silly magic of the holiday. But I couldn’t help but notice that our home was smothered in wreaths, garlands, poinsettias, and twinkle lights. Carols played ad nauseam, flooding our home with the spirit of Christmas—while there was nary a trace of the spirit of the Hanukkah story.

As much as I’d fought against it, I was at times, unwittingly, still my father’s daughter. As I hung all our vintage stockings on the fireplace mantel, I looked over and saw a lone menorah sitting like a dried-up, forgotten plant on a table in a dim corner of the family room—as dark and set apart as that street where “they” lived.

9

Mississippi Baby

I’m the only actress in the history of show business who lost a part because she slept with the director. I was cast in my husband’s film Miss Firecracker, but by the time they got around to shooting a year later, I was too pregnant to play the role. Rubbing salt into that oozing wound, I had to move, relatively last-minute, to Yazoo City, Mississippi, for two months to be with him for our baby’s birth. So with my new seventy pounds of baby I relocated—in June—to the deepest bowels of the South. It’s a debt to me that Tommy is still paying off.

Being eight months pregnant in the middle of summer in Yazoo City was like being eight months pregnant on the planet Mercury. Having never spent any time in the South, it felt like a wildly different planet. Tommy had to work sixteen-hour days. I knew no one there. A tsunami of homesickness hit me within the first few hours.

You could taste that particular kind of heat, not unlike tasting somebody’s meal after it’s been left outside in the sun for two weeks. The streets were eerily empty and quiet; there was no small talk from the mailmen. Even the neighborhood dogs just did their business and got the hell back inside. I rarely ventured out of our violently air-conditioned house my first week there. Even my short waddle down the sidewalk to our car left me dripping wet and ready for a nap.

One day our unborn baby and I had escaped into our usual sleep-stupor when Tommy came home from shooting and reminded me that our due date was in six weeks. Somehow, in the middle of this miserable hellhole, I needed to pull it together and find someone who would deliver our baby.

We both wanted a natural birth for a lot of reasons, mostly because the Lamaze classes we took in New York brainwashed us into thinking any pain medication would shrink our baby’s brain to the size of a gnat. Besides, I loved the image of myself as the Earth Mother goddess that I saw in all my hippie birthing books, squatting in a field of golden wheat, backlit by the setting sun. It excited me that I might have that kind of pioneer-woman strength. More than all of that, though, I didn’t want to be my mother. She’d been knocked out by general anesthesia for all eight of her C-sections—six babies and two stillborns. She was a vessel, sliced and diced, never a participant, never in control. I wanted control, no anesthesia, not even an epidural. Everyone knew epidurals were for sissies.

Luckily, right away we found a midwife in nearby Jackson who was a progressive feminist. But we still needed to choose our doctor . . . and quickly. The first one we met looked like he belonged on a box of Kentucky Fried Chicken; chubby, with a short white beard and a rosy face as if he’d just chugged a fifth of Jack Daniel’s. He seemed a little too impressed by my being a “celebrity.”

“Well, Christine and Tommy, we’re all so honored and excited that you came all the way down to Mississippi to have your baby! Especially since it has the highest infant mortality rate in the country!” He leaned forward across his messy desk and touched my hand. “But don’t you worry, sweetheart, you’ll be just fine.”

Yes, I will be fine, as soon as I get the hell out of your office!

I’d wanted to come down here to support my husband, but I had a brilliant obstetrician who I adored back in New York City, and the doctors we met down here—all male—validated every prejudice I had about the South. One of them shook his head as we expressed our desire for a natural birth, glaring at us as if we might be part of some kind of satanic cult. Finally we found one who agreed, but he had a signed photo of himself with his arm around George Wallace on the wall of his office. I just couldn’t.

Time was running out; our baby could arrive any day now. I started thinking I’d made a huge mistake ever leaving New York. Then we met Dr. Beverly McMillan. A female doctor in Mississippi? Had the heat caused me to hallucinate her? She had a delicate-looking face with no-nonsense short-cropped brown hair. Her Victorian house, perched on a green hill overlooking Jackson, was decorated with faded Persian rugs and antique furniture. She served us tea in vintage floral china cups with perfectly unmatched vintage saucers. We sat in her wood-paneled library with its Tiffany lamps and its floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. I watched her closely as she sipped her tea; her little finger charmingly stuck straight out.

We made our pitch and then eagerly awaited her response. She put down her cup and, in a warm southern draw

l, said, “I am so impressed that y’all want to do this naturally. I’ve been trying to encourage my patients to do it this way for years, but they are very resistant. It’s like the women’s movement hasn’t made it this far south yet.”

Practically crying with relief, Tommy and I smiled at each other; we had found our gal! After we said our good-byes, we almost skipped down her crunchy gravel driveway, which was where we saw the bumper stickers plastered all over a red pickup truck parked there.

Abortion is murder

Pro-life saves lives

Abortion is the ultimate child abuse

Guns don’t kill people, abortion clinics do

I’d been a prochoice activist my entire adult life. Tommy shared my view that protecting women’s reproductive freedom was of dire importance. So we stood in silence for a few seconds before heading straight for our car.

“I think a storm is coming in,” said my husband as he pulled onto the road.

“That would be nice. Might cool things off a bit,” I muttered, my arms tightly folded on my whale lap.

We drove for about a minute. Then Tommy said, “Look, I know we don’t have any more time, but maybe we should think about looking for another doctor . . .”

“No, I know. I agree. I mean, we have to. Absolutely,” I said, stepping on his words.

“Or maybe you should think about going back to New York,” he said sadly.

“But I really want us to be together for this! Besides, I’m not sure any airline will let me fly this late in the game.” I looked down at my near-bursting belly. A foot the size of my thumbnail kicked me hard. I saw it bulging through my tight T-shirt. I gasped. He looked over at me. I looked at him. By the time we got home, we decided that the truck couldn’t possibly belong to Dr. McMillan. She was a sophisticated, liberal, pro-woman doctor with great taste in interior decorating!

So, our doctor chosen, I spent the next few weeks hanging out on Tommy’s set. It was 103 degrees, 100 percent humidity. My enlarged inner thighs made loud sweat-slap sounds with every step I took. Scared to move because I might ruin a take, I sat there, trapped, wondering how many other parts I’d have to turn down because I had a child. Tommy promised me I wouldn’t have to give up my career, but what did he know? He was a man. He wasn’t the one who had to watch another actor play the hell out of his part. He didn’t have to munch on roll after roll of fruit-flavored extra-strength Tums to try to ease his chronic heartburn; he wasn’t the one worried he might distract the actors with the sound of his wet flabby thighs.

A few days later, I woke up from a nightmare. I dreamed that I didn’t have a baby inside me but rather a little yellow duck—an actual fluffy baby duck. Upset, I jumped out of bed, and suddenly my water broke, a week early.

Tommy and I rushed to the hospital in Jackson. We were taken to our private “birthing room.” I had envisioned something spa-like; softly lit, painted in warm neutrals, with antique furniture and an appropriately faded Persian rug. But this one had insulting ceiling lights and was decorated like a girlie-girl’s fantasy bedroom; all pinks and yellows, with painted flowers, kittens, and yes, baby ducks smothering the walls.

For the first few hours I thought, Hey, come on, this labor stuff isn’t so bad. Are all these southern women just a bunch of wusses? What are they so afraid of? Maybe they don’t have decent Lamaze classes down here. Perhaps they didn’t learn, like I did, that pain could be mastered simply by being in charge!

Then, by about the tenth hour, things started to get real. Sadly, that breathing technique we’d practiced for months turned out to be a heinous lie, like being told to just take an aspirin after being hit by a train.

“Owwww! It feels like he’s punching his way out of my lower back!” I yelled. Our strong midwife rubbed my back then handed me a tennis ball. “Here, Christine. This should help. Just gently roll back and forth over it.” I knew she meant well, but in that moment, all I wanted to do was take that ball and gently shove it up her ass.

Nurses’ heads kept popping into our doorway. All their southern accents sounded exactly the same, like they were in an episode of The Andy Griffith Show.

“Oh, honey, are you okaye? Can Ah offer you something to make you more comfortable?”

“No! I’m not doing any of that! I told you guys!” I screamed. “I’m fff . . . ahhh . . . ine!”

“Okaye,” she replied, sighing deeply, as if I’d said I was jumping out of a plane without a parachute.

About an hour later, another nurse came in. “Excuse me, sir. What is going on? We are all very concerned. It sounds like someone’s dah-in’ in here!” She had to yell to be heard because by this point I was screaming bloody murder. “Look, Ah’m terribly sorry, but some of the other women are complainin’. Do you think you could get her to take something?”

Jesus Christ. This was a women’s hospital. Yet all they wanted to do was shut us up. I proceeded to bellow so loud, I was sure I scared the other newborns on my floor back up the vaginas of their sedated mothers.

After twenty hours of trying to push a house past my cervix, my teeth chattering, my entire body started to go into convulsions. Beginning to panic, I breathlessly asked my husband, “Remind me again why we decided to do this naturally?!” Just then the doors opened and in walked Dr. McMillan, who had been in and out all day, checking on my progress. I immediately begged her to give me some drugs—“Just something mild that won’t make the baby’s brain shrivel up!” She gently took my hand and offered me a sedative called Stadol.

“This should just take the edge off a bit,” she reassured me.

“yes, please! now!” I cried. I knew I was letting everyone down; our son, our midwife, the Lamaze trainers, my husband, and myself, not to mention the entire women’s movement, but I didn’t give a shit. Within seconds it put me to sleep, only to be woken up by a magnitude 9 earthquake in my uterus every few minutes. Loopy and completely out of control now, I felt at the mercy of Dr. McMillan.

After working painstakingly to get the baby into a proper position, she at long last asked me to push, three times. But by this point, I wasn’t focused on pushing out a baby; I was just trying with all my might to push out the pain.

Finally, after twenty-two hours of labor, our son arrived. As he lay peacefully on my stomach, both of us beyond exhaustion, I looked down and saw that he was perfect; the opposite of a duck. Standing around me I noticed our heroic and patient doctor, our hardworking midwife, the worried nurses, and my husband, who had tears rolling down his cheeks.

I felt such gratitude toward the entire staff. That is, until they started making fun of our baby’s first name, which we had chosen carefully so he wouldn’t be teased like young Tommmmeeee Schlammmmmeee had been.

In fact, we’d spent months trying to figure out what he was going to be called. It had seemed completely absurd to me that our child would automatically be given his father’s last name. Of course, we had the hyphenated option, but both Lahti-Schlamme and Schlamme-Lahti sounded dreadful, as did the combo “Schlahti.”

I’d said, “You know, honey, I think we can both agree that Lahti is a prettier sounding name.” Slam dunk, I thought.

Then my husband reminded me, “Well, that may be true, sweetie, but as you know, most of my relatives were . . . uh . . . exterminated in the concentration camps, so . . . um . . . you know . . . there are very few Schlammes left.” He played the Holocaust card. Those fucking Jews!

But in spite of all that agonizing over his name, within the very first hour of our son’s Mississippi birth, we heard, “Wilson Hugo Laydee Schlam? Why don’t this baby have a first name? Which one is his last name?” It was asked by a stocky, thick-necked nurse as she read his chart. We could hear her chortling all the way down the hall. I hugged my baby close to my chest. It was time to pack our bags and get the hell out of Mississippi.

Several years later, Tommy and I were back in our beloved Upper West Side apartment in New York. While reading the Sunday Times, we noticed an article

about a man named Roy McMillan from Jackson who was a self-proclaimed “abortion abolitionist.” He was quoted as saying, “It is not a sin to kill abortionists.” He would harass the patients at the local clinic by yelling in a child’s voice, “Please don’t kill me, Mommy! Keep me away from all those bloody hands!” He’d then throw little plastic naked babies into their car windows, or if that didn’t work, he’d show them Ziploc bags of severed fetus parts.

“McMillan, McMillan,” I said, “that sounds familiar.” We turned the page and saw a picture of him with our beloved ob-gyn. “Oh my God, that’s Dr. Bev McMillan! Holy shit! That was her fucking truck!” Apparently, after opening the first abortion clinic in Mississippi, she saw the born-again Christian light and joined her husband’s radical mission. In that moment I was horror-stricken; the first hands that touched my baby were the hands of a right-wing nutcase who believed sperm were squiggly children!

“Oh, those motherfucking self-righteous assholes! How dare she not tell us this before we agreed to—” I started to rant.

Then I heard our toddler playing across the room. I watched him toss each of his favorite Beanie Babies, sending them soaring into the air, then erupting with giggles as stuffed unicorns, bears, and giraffes rained down onto his tiny body.

In that instant, I knew that if I ran into Dr. McMillan on the street, I would have to hug her. When we needed her, we were certainly able to put aside the fact that she was rabidly antichoice. After all, it was her capable, life-giving hands that brought our son into the world.

Wilson Hugo Lahti Schlamme, I am proud to say, has grown up to be a gifted artist, and a prochoice feminist. Late at night, there are times I can’t help but wonder if his occasional, unfortunate tendency to watch Fox News has something to do with where he was born. But as I picture our remarkable, tender son, there’s no question that my husband’s debt to me was paid off a long time ago. And then some.

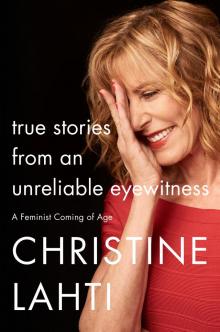

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness