- Home

- Christine Lahti

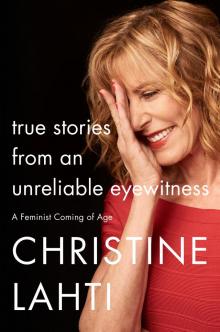

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness Page 4

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness Read online

Page 4

“So nice to meet you, Christine! I’m Michael. Please, come in.”

Dressed in a stylish suit and tie, my date seemed polite and gracious. He looked about forty years old, had thick black hair, and stood at least a head shorter than me, even though I purposely wore flats. I instinctively slumped a little.

“Please sit down! Would you like a glass of champagne?”

Soft beiges and creamy whites drenched the spacious room. I’d rarely been in a place like this that didn’t have plastic covering the furniture. While sipping our Dom Perignon, we discussed politics, his brilliant career, and my promising career. Patty was right—he just wanted some company! This felt completely legit and fantastic. Twenty minutes went by, then thirty, then a whole hour. The call never came.

“Hey, Michael, why don’t we go to dinner now? I’m getting really hungry.”

“I’m so sorry. I don’t know why he is so late!”

“Well, your friend is pretty darn rude, keeping you waiting like this.” I emptied my crystal tulip champagne glass.

“I couldn’t agree more.” He refilled my glass with the rest of the bottle.

“Fine, can we at least order room service?”

He dialed, ordered filet mignons and a bottle of cabernet, and hung up the phone.

“Hey, Michael,” I said, “parlez-vous français?”

“No, why do you ask?”

“Nothing—I just wondered.” I smiled as I sank back into the plush couch. He sat down next to me. I noticed his girlie-smelling cologne for the first time.

“I want to know more about Christine. What’s it like in . . . the Midwest?” he inquired, as though he was asking about Disneyland.

“Ohhh, well, it’s beautiful, lots of lakes. It’s called the Water and Winter Wonderland,” I added proudly.

“Really? Isn’t that fascinating! So tell me, what’s a nice girl like you doing in a job like this?”

“Yeah, right . . . wait, what do you mean?”

“Come on, you know what I mean. This is an escort service.” He put his arm around me.

My proper Lutheran upbringing flashed before my eyes. Oh dear God, where did he get that I was a . . . I’m going to kill you, Patty!

“Oh boy. There’s been a huge misunderstanding here, Michael. My friend told me that . . . this was just a . . . uh, never mind.” I grabbed my purse and coat. “I have to, uh . . . I have to go.”

“No, wait, don’t.” He inched even closer; I sprinted to the door. He glared at me and reached into his pocket.

Oh my fucking God, is he going for his gun? Am I about to be raped at gunpoint, or murdered? I ran to escape and opened the door to the . . . bathroom. Shit. I slammed the door. I locked it. Oh God, what should I do? My heart was beating out of my dress. He started to knock on the door.

“Please just let me go!” I begged him. “I’m really sorry, I didn’t know what this job was! I’m not a hooker!”

“It’s okay, Christine, you can leave. Just come out of the bathroom.” Finally, I emerged, armed with the toilet plunger. He reached into his pocket again.

“No, please don’t shoot!”

“Jesus Christ, calm down! I’m just getting out my wallet to pay you your twenty bucks!”

But the drama queen in me knew better. I flew past him, through the correct door, and down the hall so fast my feet barely touched the carpet. Even though I was an agnostic, I prayed, Oh, Jesus, God, Lord, Savior, whatever your name is . . . if I can just please get down this elevator alive, I’ll believe, I’ll . . . believe!

When I got down to the lobby, I rushed to the public phone. As I waited for Patty to pick up, I noticed my image reflected in the marble. I saw an awkwardly lanky young woman, huddled over the phone, with wet stains under the arms of her cheap rayon dress.

No one answered. I hung up. It probably wasn’t even a big deal to my “free love” friend Patty. Or maybe she just had a tendency to believe, the way I did.

I’m aware that being so adept at the art of make-believing has also had its benefits. Later in life, this skill would help me to stand on a bare wooden stage and imagine I lived in a castle in Elizabethan England. Or on a plantation in the Deep South. It would help me to become a Hungarian Holocaust survivor. A spinster southern belle. My ability to immerse myself in imaginary circumstances has enabled me to get inside the skin of a whole variety of characters and make a good living while doing it.

Thankfully, over time, I’ve discovered that the suspension of disbelief is different, and a lot less dangerous, than naïveté. But in that moment I was just a gullible young woman with stars in her eyes and sweaty armpits who desperately wanted to believe she was so much more than just someone’s escort.

I buttoned up my wool green coat. I walked out of the fancy hotel. And on the packed subway ride home, I couldn’t stop thinking about how nice those twenty dollars would have been. I picked at the tiny run in my $2.95 panty hose, a run that soon would become a fleshy four-lane highway down my entire leg.

4

Hidden

Even back then, when I was twelve, it didn’t look all that special—just a flurry of high weeds on the bluff near the road. The grass was flattened by my sprouting bean-pole body huddling there—as if a deer had slept on it. The air was thick with dazed insects barely able to move in the Michigan summer. The only sounds were the screeching of cicadas and the occasional whoosh of a speeding car going by. At least I could see the lake from my hiding place. On the rare sunny days, it was a slash of turquoise, but usually the water was as flat gray as the sky. The spot was only minutes from our summer cottage in Bellaire, Michigan, but it felt like miles. It took me forever to get there through the tangled undergrowth. But none of that mattered: what was important was that when I was there, nestled in among the brambles and wildflowers, nobody could see me.

Privacy was at a premium in our cottage. My three sisters and I shared one small bedroom. The slanting ceiling of the A-frame forced us to walk hunched over like preteen grandmothers. We were separated from our brothers’ room by a thin knotty-pine wall that rose only three-quarters of the way to the ceiling. At any time, day or night, their devilish eyes could be seen peeking over that wall. This secluded hilltop spot became my secret refuge where I could go to get away from all of them—and, most importantly, to be sad.

Sadness was not well tolerated by my family; my parents simply didn’t believe in it. Growing up, I watched as they drank “Torch Lake Specials”—lemonade, whiskey, blue curaçao, and maraschino cherries—every night to wash away any trace of theirs. In our family you were expected to be happy. Being quiet was acceptable, too, but if you were downhearted, you were to go to your room and wait it out.

On the wall behind my sisters’ and my two double beds were our role models: four framed faces of the beatific girls featured on the packages of Quilted Northern toilet paper. They were all doe-eyed, smiling, each holding a blanket, a bunny, a kitten, or a bouquet of pansies up to her painted pink cheek. Each sister had the picture of the girl she most resembled above her side of the bed. My doppelgänger had long brown hair and hazel eyes, just like me. They served as a kind of not-so-subtle reminder that it was our duty to be just like them.

In my lakeside sanctuary, there was no pressure to emulate one of those toilet-tissue cherubs, squeezably soft and pliable. Instead, I got to just sit in whatever I was feeling and savor it, as rich and sweet as caramel.

In Housekeeping, a movie based on Marilynne Robinson’s novel in which I played the character Sylvie, there was a scene where she was confronted by a gaggle of town ladies concerned that Sylvie’s nieces looked sad. She responded sharply, “Of course they’re sad. They’ve lost their mother. They should be sad!” The ladies looked at Sylvie like she should have been locked up. I always thought about that scene whenever I remembered how uncomfortable sadness was for our family, as unwelcome as a drunk uncle showing up uninvited at Thanksgiving.

I first felt the exquisite snag of a broken heart

while sitting alone and quiet in my refuge. It was also where I first cupped my hand over my breast and noticed how, quite suddenly, my body was different. I was there when I practiced kissing on my forearm, with my eyes opened and then closed, with tongue, then without. That spot held the secrets of my big plans about how I’d someday fully escape from the chaos of my family.

No one ever knew about my secluded place until almost fifty years later when I returned, excited to share it with my husband. It seemed so silly—almost embarrassing—as I pointed it out to him. The trees across the road were so mature that there was practically no view of the lake. The weeds looked shorter, like no one could have ever been concealed by them. The once flattened grass stood straight and tall. The hill seemed barely a hill at all, more like a small bump in the flat terrain. The road had become a highway, its traffic noises louder, more constant. There was no trace of the hidden girl who sat alone there. Her secrets, as exposed as her former hiding place, had long since vanished.

The wind bent the tops of the birches, revealing the lake at its most heart-stopping blue. I sat here with my partner of nearly thirty years, neither of us talking; gratefully visible now, in this ordinary place, just a stone’s throw away from our family’s cottage on the lake.

5

Walking

It was a crisp autumn morning in New York City in 1973. As a twenty-three-year-old hippie-meets-serious-actress-wannabe, I knew that doing a television commercial was beneath me. However, my most lucrative acting job to date had been an off-off-off-off-Broadway play that paid in subway tokens, and being a waitress had lost a lot of its bohemian allure. After pounding the pavement for almost two years, still without an agent, I was thinking I could probably handle a little selling out.

So I prepared to go to an open audition for two national commercials. I reluctantly parted with my beloved armpit and leg hair. I threw on some dime-store makeup and packed myself into the rush-hour uptown subway. I met with the casting director, John Anderson—middle-aged, disheveled, and hair-challenged, but he seemed professional and polite. We talked briefly. He took a few pictures. I left.

Two days later he called me and asked me to come back in for a callback! I’d received feedback that I needed to look more conventional, so I hot-rollered and Aqua-Netted my frizzy hair into a large sticky helmet. I put on my polyester three-piece suit, which had the texture of a car tire. I glanced in my cracked antique mirror and decided I looked like Tammy Faye. But I sucked in my gut, yanked up my control-top panty hose, slipped on my height-minimizing flats, and headed out to change the course of my life.

I arrived at Mr. Anderson’s office on Seventy-Fifth Street and Lexington twenty minutes early. He swung the door open.

“Christine Lahti! Come on in, sweetheart. This is your lucky day. Guess what? You got the gigs!”

At first I thought he’d mixed me up with someone else. I stood there, skinless. “What? Really? Are you sure?”

“I’m sure,” he said, smiling.

“But how? I mean, thank you so much, Mr. Anderson, but I haven’t even auditioned for them yet!”

“John, call me John, come in!” He let me into his reception area. “So . . . I showed your pictures to these two director friends of mine, and you’re just the type they are looking for!”

A weight suddenly lifted from my chest. I was going to finally be a professional actress! And two national commercials—that could pay my rent for years. I could quit my fucking waitress job!

“Really, Mr. Ander— I mean, John? You have no idea what this means to me!” I asked him if he wanted me to read.

“Oh, no, you don’t have to audition, the commercials are already yours!”

I couldn’t believe it. I crossed all my fingers inside my pockets as he took my arm and walked me into his inner office. He sat down at his cluttered desk, picked up a used tissue, and wiped his forehead with it.

“Have a seat, Christine.” He leaned back in his chair. “First of all, you should know you stand to make at least ten grand a piece on these, and with residuals . . .”

I stopped listening and instantly pictured my new cockroach-free apartment with its separate bedroom and window air-conditioning unit.

“Holy shit! I mean . . . sorry, John, but this is so incredible! So when do I . . .”

He shuffled some papers on his desk as he said, “Well, it’s really quite simple, Christine. All you have to do first is have sex with the directors.”

I froze. I was sure I misheard him, or that he was joking. He must have been joking. I laughed.

John didn’t laugh back.

“Wait, what?” I asked. “I’m sorry . . . What are you saying?” I had heard about the Hollywood casting couch for movies. But this was New York City. For two breakfast cereal commercials!

He looked at me, amused. “Look, sweetheart, this is just the way it’s done. You said you’ve got no connections in show biz, right? But hey, if you don’t really care that much about being an actress—”

“No! I do! More than anything in the world, but—”

“Look, it’s no big deal, everybody does it. Dunaway, Fonda, Collins . . . all of ’em. It’s just a reality for someone like you, sweetheart.” He chuckled, as if he couldn’t believe anyone could be so naive.

I sank lower in my cold metal chair.

“Look, let’s face it, Christine.” He gazed at the curvature of my nose. “You’re . . . uh . . . well, an unconventional type. And what are you, almost six feet tall?” He said it as if accusing me of murdering both my parents. “Well, how the hell else do you think you’re going to make it?”

“I don’t know . . . I thought . . . that I was . . .”

“Let me guess, talented and a hard worker? Or do you think you’re going to make it on your looks?”

“No . . . no, of course not . . . but I just . . . I thought you said I . . . I mean, how could you think that I would ever . . . I mean . . . I . . . I . . . I . . .” I started crying and couldn’t seem to stop, so I grabbed my headshot and tore out of his office. As I pummeled the elevator button in the hallway, I heard him yelling through his door, “Hey, Christine, you’re a fool if you think you’re going to make it any other way!”

The elevator hurled me down to the lobby. The revolving glass door spat me out into the street. I felt lightheaded. I just wanted to go home, but where was I? What street was this? A cab went by—no, I couldn’t afford that. Besides, I still couldn’t quit bawling. So I began the seventy-five-block trek back to my apartment.

I started heading down Lexington Avenue. When I got to Seventy-Second Street, tears dribbling down my nonabsorbent jacket, I could barely see where I was going. An assault of fire engines and ambulances went by, and over their sirens, I started talking out loud to myself like a lunatic. “Oh God,” I gasped between sobs. “What if he’s right? Does this mean I’ll never get to be an actress?” A woman walking next to me with her baby stroller noticed and suddenly pulled away. “What the fuck you looking at, lady?” I barked at her.

As she darted across the street, I heard smooch, smooch and a piercing whistle. I looked up and a construction worker called out, “Hey, pretty girl come here, I wanna lick you.” Jesus. I picked up my pace. “Hey, where ya goin’, hot stuff? Smile! Whassa matter—you can’t smile?” Smile? What was he talking about? But sure enough, as I lowered my head, I found my face contorting into a kind of automatic grimace.

Then at Sixty-Third Street, I realized that I was still carrying my pathetic headshot. I looked down at it. When the hell did I become my mom? The made-up face, the perfect hair, the phony smile. This was the way she always looked, even when my dad, all of us, made fun of her, laughing at her opinions, about . . . everything.

As my tears fell into little glossy puddles on the eight-by-ten, I stared at my image. No wonder I can’t get an agent, I thought. I had hideously small ferret eyes, my nose was way too wide at the top, and it actually hooked to the left at the tip. I looked like a man in drag. And I w

as too fucking tall! What was I thinking? Forget “unconventional.” Everything about me was just . . . wrong.

At Fifty-Seventh Street, I headed west and saw Carnegie Hall. My heart still pounding, I wasn’t sure I’d ever get home. A tall, confident-looking young woman with a briefcase walked by me and for some reason laughed. Was she laughing at me? At the four layers of mascara that had run down my splotchy red cheeks? When I left my apartment this morning I felt like her. Or maybe I just thought I did.

My dad’s advice from when I was in high school suddenly echoed in my ears again. Why buy the cow, Chris, if you can get the milk for free? It wasn’t until that instant that I truly understood my girl-value. I wish I’d said “Well, Dad, why buy a whole pig, just to get a little sausage?” But I didn’t. I just shut up and went back out to pasture.

Somewhere near Forty-Eighth Street, a silver-haired businessman walked by and perused my body like it was an item on his à la carte dinner menu. I instantly pictured the silver-haired professional actor Chester Martin, and that memorable night when he offered me some of his sage career advice: “Look, Christine, you have absolutely no light to shed upon the human existence. Your desire to be an actress is a pipe dream, I’m afraid. You have no hope of making it as a professional.”

He was from Nebraska, although his accent was distinctly British. I considered for a second that he was saying this only because I hadn’t let him fuck me the previous night. But then I decided that no, he was simply being brutally honest.

Close to Times Square now, the fumes from Papaya King pulled me in. I decided to drown my sorrows in a super-duper-deluxe hot dog. As I stuffed the tube of meat paste with its permissible percentage of pig snouts and 480 milligrams of salt into my mouth, I looked up. All I could see were gigantic billboards of nearly naked women with bodies that would have made a Barbie doll jealous. They all looked like they were having sex with Mercedeses, Marlboros, and bottles of Johnnie Walker Red. Then I noticed a flood of men pouring out of the towering office buildings and a stream of women trickling out behind them. I thought of college, of all the marches for civil rights and equality, when out of sheer habit, we girls marched behind the men. We made the peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, and they made all the speeches. I even turned down directing a play in college because I wasn’t comfortable telling boys what to do.

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness

True Stories from an Unreliable Eyewitness